With origins in mechanical aids and early calculating devices, you can explore how the first computers evolved from tools like the abacus and Babbage’s Difference Engine to electronic machines of the 1940s; this history shows how your modern devices emerged through innovations by pioneers such as Ada Lovelace, Charles Babbage, Alan Turing and the teams behind ENIAC, shaping computation, industry and everyday life.

The Concept of a Computer

You see a computer as a system that accepts input, executes programmed instructions, stores results, and produces output; Babbage’s Analytical Engine (1837) first separated “store” and “mill,” while Turing’s 1936 paper defined computability with an abstract machine. Practical designs fused binary representation, electronic switching, and the von Neumann stored‑program idea (1945). In practice your devices implement those same layers—data representation, control flow, memory and I/O to turn instructions into reliable results.

Early Mechanical Devices

You can trace computation back to the abacus (c.2400 BCE) and the Antikythera mechanism (~100 BCE) for astronomical prediction; Blaise Pascal’s Pascaline (1642) automated addition, and Leibniz’s stepped drum (1673) extended multiplication. Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine (1822) and Analytical Engine (1837) introduced programmability via punched cards, giving you the first blueprints for machine-based calculation rather than mere aids.

The Role of Mathematics

You depend on mathematical foundations: Al‑Khwarizmi (~820) formalized algorithmic procedures, Leibniz (1703) promoted binary, George Boole (1854) created algebraic logic, and Alan Turing (1936) defined computation with his Turing machine. Claude Shannon (1938) then mapped Boolean algebra onto switching circuits, so you can convert logical expressions into physical electronic designs.

You should note deeper formal links: Church’s lambda calculus (1936) and Turing’s model led to the Church‑Turing thesis asserting equivalent notions of computation, while von Neumann’s 1945 architecture translated those theories into stored‑program machines. Algorithmic complexity emerged later—Cook and Levin (1971) defined NP‑completeness—so when you evaluate algorithms you rely on both correctness proofs and complexity bounds grounded in mathematical theory.

The Evolution of Computing Machines

Charles Babbage and the Analytical Engine

Designed in 1837, Babbage’s Analytical Engine introduced a general-purpose mechanical architecture: you find a “mill” (processor) and a “store” (memory) intended to hold 1,000 numbers of 50 digits each. He proposed punched cards from the Jacquard loom for programmability, and specified conditional branching and looping, so you can see direct ancestors of control flow and the separation of CPU and memory. Although never completed, its blueprint anticipated key principles of modern computers.

Ada Lovelace: The First Programmer

In 1843, you encounter Ada Lovelace’s extensive notes on Luigi Menabrea’s paper, where Note G contains a step-by-step algorithm for computing Bernoulli numbers on the Analytical Engine—the first published machine algorithm. She argued the Engine could manipulate symbols beyond arithmetic, predicting applications in music and art, and her work established algorithmic thinking that you can trace to modern programming.

Born in 1815 and tutored by Mary Somerville and Augustus De Morgan, Ada combined rigorous math with visionary commentary; when you compare her translation and notes to Menabrea’s original article, her commentary is roughly three times longer and contains detailed operational tables and flow of computation. You can point to her discussions of subroutines and looping as early conceptions of software structure, and although the Engine was never realized in her lifetime, your view of programming’s origins often starts with her contributions.

The Birth of Electronic Computers

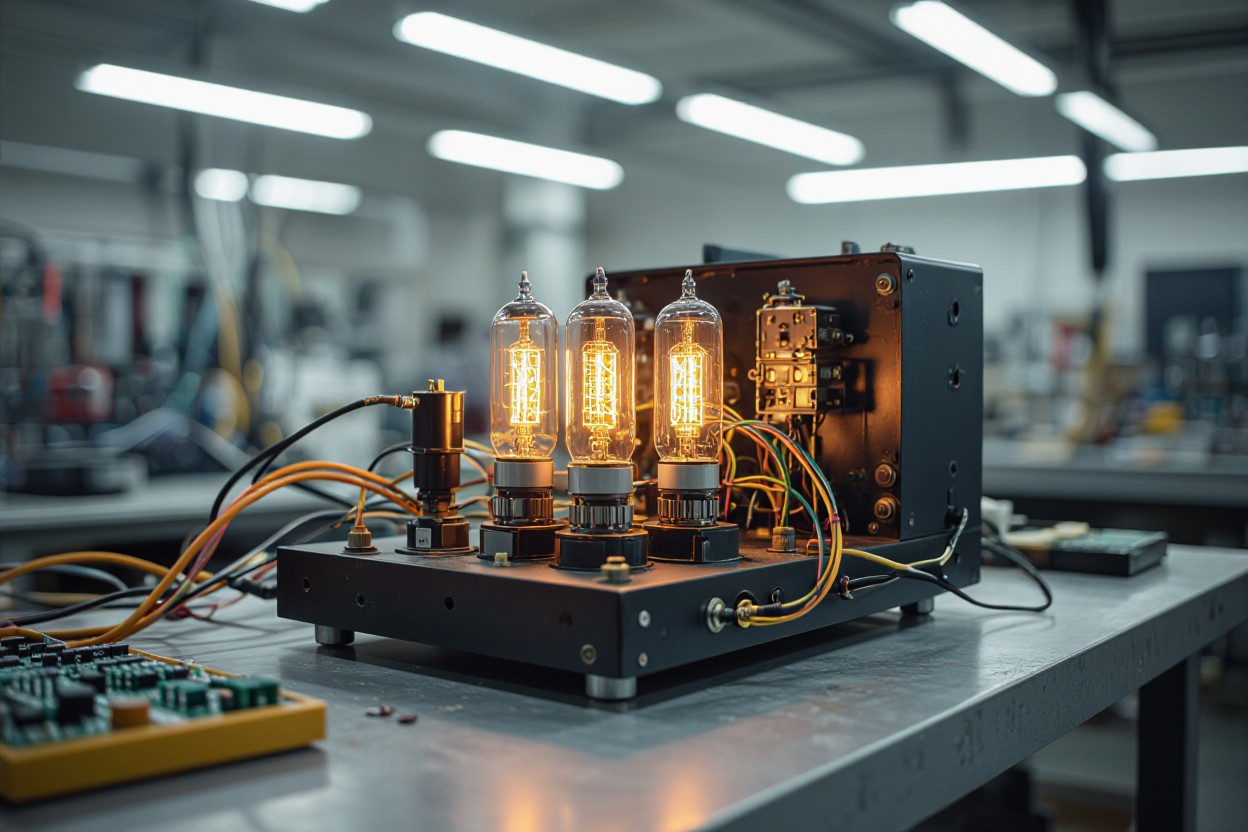

In the 1940s you saw computing shift from mechanical gears to electronic circuits, driven by wartime demands and research labs. Colossus (1943) processed encrypted German messages, while vacuum-tube machines like ENIAC (completed 1945) demonstrated programmable numeric work. By measuring operations per second and physical scale, engineers established performance baselines that guided postwar designs and commercial adoption in the 1950s.

The ENIAC: A Milestone in Computing

You encounter ENIAC as a turning point: finished in 1945 by Mauchly and Eckert, it contained 17,468 vacuum tubes, occupied roughly 1,800 square feet, and performed about 5,000 additions per second. Originally built for artillery tables, it later aided weather and nuclear calculations, proving large-scale electronic computation was feasible and inspiring stored-program concepts you rely on today.

Transition from Vacuum Tubes to Transistors

You trace the shift to transistors after Bell Labs’ 1947 invention by Bardeen, Brattain and Shockley; by the mid-1950s manufacturers deployed junction transistors in business machines. Transistorized systems cut size and power dramatically, raised reliability, and enabled computers like the IBM 1401 and DEC’s PDP-8 to reach broader markets and new use cases in industry and academia.

You also note that the MOSFET (invented 1959) and early integrated circuits (Kilby 1958, Noyce 1959) accelerated scaling, letting transistor counts soar and costs fall. Mean-time-between-failures moved from mere hours in vacuum-tube rigs to thousands of hours in transistor systems, and machines like the PDP-8 sold in the tens of thousands, showing how the transistor made computing accessible beyond laboratories.

The Development of Personal Computers

Microprocessors and kit culture shifted computing out of labs and into garages, so you witnessed the transition from mainframes to devices hobbyists could own. By the mid-1970s Intel’s 8080 and MOS Technology’s 6502 drove prices down—6502 chips sold for about $25—letting innovators build affordable machines. Companies began selling assembled units alongside kits, and your options expanded from DIY Altair builds to ready-to-run systems that set the stage for consumer adoption.

The 1970s Revolution

By 1975 the MITS Altair 8800 sparked a hobbyist boom, and you felt the momentum at Homebrew Computer Club meetings where the Apple I (1976) was demonstrated. When Apple, Commodore and Tandy released the Apple II, PET and TRS-80 in 1977, those “1977 trinity” models made computing accessible to small businesses, schools and enthusiasts, accelerating software development and lowering barriers for your first purchase.

Rise of Home Computing

Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s you saw home machines shift from curiosities to household staples: the Apple II supported VisiCalc (1979), while the Commodore 64 later sold around 17 million units, becoming a gaming and learning platform. Affordable hardware and bundled BASIC interpreters meant you could program, play and learn without institutional support.

Software ecosystems cemented that shift: Microsoft BASIC licensing, floppy drives (5.25″) from Shugart, and expansion slots on the Apple II let you add disk controllers, printers and modems. Small businesses adopted spreadsheets, schools used educational titles, and bulletin-board systems emerged as you connected via modems—practical use cases that transformed personal computers into indispensable tools for work and home.

Impact of Computers on Society

Changes in Communication and Work

You rely on networks that connect over 5 billion internet users and carry more than 300 billion emails daily; real-time tools like Slack, Microsoft Teams and Zoom (which jumped to roughly 300 million daily meeting participants in April 2020) transformed meetings, project tracking and client support. Industries from banking to journalism automated workflows, and many firms shifted to hybrid models, cutting office time while boosting global collaboration across time zones and contractors.

Influence on Education and Research

You now access courses and primary sources that were once rare: Coursera surpassed 100 million learners by 2021, MIT Open Course Ware publishes some 2,400 courses, and databases such as PubMed host over 35 million citations. Digital labs, cloud-based simulations and virtual classrooms let your institution scale enrollment, run remote experiments, and grant students worldwide access to curated curriculum and peer networks.

You see research cycles compress as computing enables massive data sharing and automated analysis: Alpha Fold released predicted structures for over 350,000 proteins, accelerating structural biology; CERN’s Worldwide LHC Computing Grid links thousands of institutions to process petabytes of collider data; and during the COVID era tens of thousands of preprints and datasets circulated online, letting teams iterate on vaccines and epidemiology models in weeks rather than years. Your classroom benefits similarly AI-driven tutoring, interactive simulations and learning analytics personalize pacing, while open repositories and APIs let you integrate real datasets into coursework for hands-on research experience.

Future Directions in Computing

Quantum Computing

With qubits you can tackle problems classical CPUs struggle with by exploiting superposition and entanglement; current hardware superconducting machines like IBM’s 127-qubit Eagle and trapped-ion systems from IonQ operate in the tens to low hundreds of qubits. Google’s 53-qubit Sycamore showed quantum supremacy for a specific sampling task in 2019. You should weigh Shor’s algorithm for factoring and Grover’s search speedups against high error rates and the need for fault-tolerant architectures, which likely delay broad practical impact by years or decades.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Transformers drive current progress: GPT-3 at 175 billion parameters set new benchmarks in language generation, and GPT-4 extended multimodal capabilities. AlphaFold’s CASP14 breakthrough enabled accurate protein-structure predictions, and reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) improved alignment in chat agents. You can apply these models to diagnostics, code synthesis, and logistics, yet must manage hallucinations, dataset bias, and substantial compute and storage requirements during training and deployment.

For deeper context, consider scaling and efficiency: large models follow predictable scaling laws doubling parameters and data typically improves performance but increases training cost nonlinearly, often into millions of dollars and requiring hundreds to thousands of petaFLOP/s-days for state-of-the-art runs.

You can reduce footprint via distillation, quantization, or fine-tuning smaller models on domain-specific labeled datasets (often tens of thousands of examples) to achieve strong results. Case studies include OpenAI Codex for code generation, DeepMind’s AlphaStar and AlphaFold (initial release covered ~350,000 protein structures), and industry deployments where model compression and careful evaluation pipelines made production use feasible while mitigating bias and safety risks.

Final Words

Summing up, understanding when the first computer was invented helps you trace how mechanical calculators evolved into electronic machines and why that history shapes your digital world; by learning milestones from Babbage’s designs and early electromechanical systems to ENIAC and modern microprocessors you gain perspective on technological progress, the forces that guided innovation, and the responsibilities you hold as a user and creator in a landscape that continues to transform society.

FAQ

Q: What do historians mean by “the first computer”?

A: “First computer” depends on the criteria: a counting aid (abacus), an automatic mechanical calculator (Pascaline, Leibniz), a programmable machine (Babbage’s Analytical Engine concept, Konrad Zuse’s machines), an electronic digital device (Colossus, Atanasoff–Berry), or the first stored‑program electronic computer (Manchester Baby). Different milestones satisfy different definitions, so there is no single universally accepted “first.”

Q: When was the first mechanical computer invented and who created it?

A: Mechanical calculating devices date back millennia (abacus). In the 17th century Blaise Pascal (1642) built a mechanical adder and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (late 1600s) improved on it with a stepped‑drum multiplier.

In the 19th century Charles Babbage designed the Difference Engine (1822) and, more importantly, the Analytical Engine (1837) a fully programmable mechanical design with separate memory and processing elements. Babbage never completed a full Analytical Engine, but his designs laid the conceptual groundwork for programmable machines.

Q: Which machines from the 20th century are considered “first computers” and why?

A: Several 20th‑century machines are cited depending on criteria: Konrad Zuse’s Z3 (1941) was the first working programmable electromechanical computer; the Atanasoff–Berry Computer (late 1930s–1942) introduced electronic digital components for solving linear equations; Colossus (1943–44) at Bletchley Park was the first large‑scale electronic, programmable machine used for codebreaking (special‑purpose); ENIAC (1945) was the first large, general‑purpose electronic digital computer, initially programmed by rewiring; the Manchester Baby (1948) was the first electronic computer to run a program stored in memory, establishing the stored‑program model used by modern computers.

Q: What role did Ada Lovelace and other early figures play in the invention of the computer?

A: Ada Lovelace wrote comprehensive notes on Babbage’s Analytical Engine (published 1843) that included an algorithm for computing Bernoulli numbers, often cited as the first computer program. She also articulated the idea that such machines could manipulate symbols beyond numbers.

Other key figures include Babbage (designs), Charles Babbage’s contemporaries and later engineers who attempted constructions, and 20th‑century pioneers like Konrad Zuse, John Atanasoff, Clifford Berry, Tommy Flowers, John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, and the Manchester and Princeton teams who turned concepts into working electronic and stored‑program machines.

Q: How did the transition from mechanical designs to electronic stored‑program computers change computing’s impact?

A: Moving from mechanical and electromechanical designs to electronic and then stored‑program architectures increased speed, reliability, and flexibility. Vacuum tubes and later transistors enabled rapid arithmetic and logic; the stored‑program concept (von Neumann architecture) allowed software to be written, modified, and reused, spawning operating systems, high‑level languages, and mass production. These advances accelerated scientific research, business automation, communications, and miniaturization, ultimately leading to personal computers, smartphones, and the pervasive digital infrastructure of today.